Open 7 days a week versus weekly closure, a huge discord among French bakers

By Rémi Héluin

In more than half of the French departments, days without bread are now ancient history. The decree imposing a weekly closure of bakeries has been repealed in 54 territories, under the impetus of the Federation of Bakery Entrepreneurs (FEB) and its members. A regulatory change that continues to maintain the fears of the craft sector, which is attached to this measure to protect the smallest structures. Whether it is a precious legacy of the past or an obstacle to the freedom of enterprise, the subject continues to divide.

On Labour Day, on the first of May, all the bakers seemed to speak in unison: there was no longer any question of imposing a day off on them, as it would harm the sustainability of their businesses. While they had previously benefited from a legal uncertainty regarding their ability to open on this day, inspections carried out in the Vendée in 2024 had highlighted the fact that bread seemed to be considered a non-essential product in the eyes of the labour inspectorate. Fears of potential sanctions have discouraged most professionals, keeping their doors closed for May 1, 2025, pending a potential regulatory change for next year.

Closures imposed to protect, an outdated idea?

This idea seems much less obvious on the side of the weekly closing day, still supported by the National Confederation of French Bakery-Pastry (CNBPF). The system dates to 1919, the year in which a law allowed the implementation of prefectural decrees imposing a weekly closing day on all businesses selling bread, whether they are artisans, warehouses, baking terminals or supermarket shelves. The objective: to preserve the economic balance between the players in the sector, allowing the natural distribution of customers between the points of sale, while offering business leaders as well as their teams a precious rest. These arguments are undermined by the reality on the ground, according to Paul Boivin, General Delegate of the FEB: "The customer consumes in all cases within his natural catchment area, or on his home-work journey. It will then arbitrate according to the quality of the bakeries located there, without considering the subject of the weekly closure."

The fact remains that the Federation must have its arguments heard in court, to obtain the abolition of the famous decrees. "This dogma is now outdated," continues the representative. All the provisions of that time have disappeared, such as the regulations on leave. Administrative case law goes in our direction, and nearly 35 million French people, in 54 departments, or 54% of the territory, can now benefit from the opening of their bakeries 7 days a week ." The entire Atlantic coast is now concerned, and some areas of resistance remain for political reasons, particularly around the Mediterranean arc.

The "7/7", a subject to be copy 5/5 to adapt to the specific reality of each company

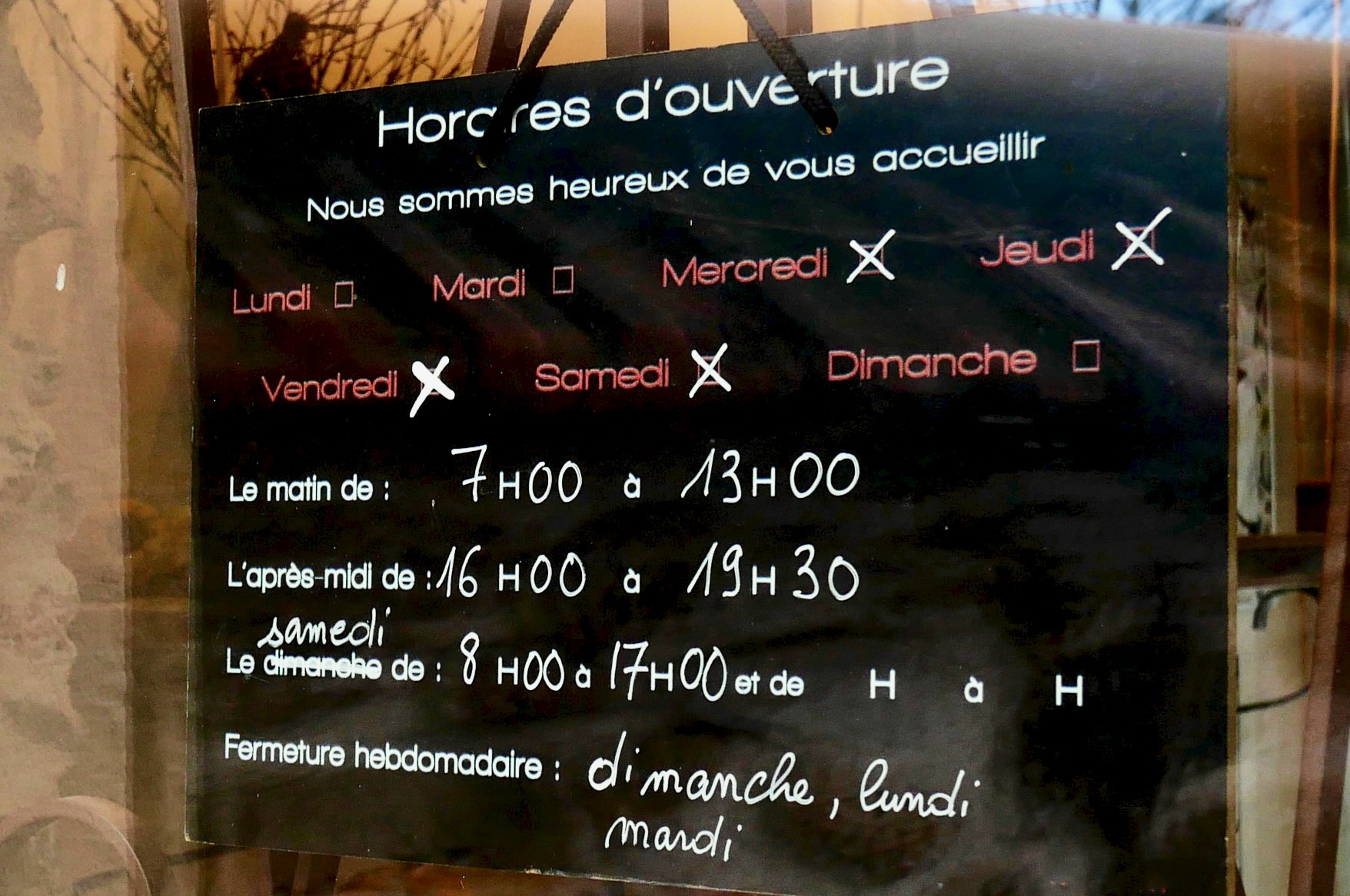

Freedom of work does not mean generalization of the practice. During the Covid period, the public authorities had implemented a temporary derogation, allowing all bakers to open their businesses all week. Many craftsmen had then adopted this mode of operation, making it possible to partially compensate for the loss of activity linked to the lockdowns. While some have taken a liking to it, even going so far as to definitively adopt the "7/7" system, including in departments subject to the famous decree, others have gone back... even going so far as to increase the number of days of closure after the pandemic. This is due to the significant recruitment and retention difficulties observed in the sector.

Franck Thomasse, president of the Syndicat des Boulangers du Grand Paris (which brings together Paris and its inner suburbs), works in a territory where the weekly closing day is still in force. In the autumn of 2024, the Paris Administrative Court of Appeal even confirmed the validity of the local prefectural decree, which was challenged by the Federation of Commerce and Distribution (FCD) and the Federation of Grocery and Local Commerce (FECP). The two organisations, which represent mini-markets in particular, claim a dominant position on the sale of bread in the capital and would like to allow their members to offer it without interruption. The measure thus retains a precious and emblematic bastion, with the risk of displeasing customers: according to a survey conducted in February 2020 by IFOP, 62% of respondents believed that bakeries in Paris should be able to open every day. "Allowing an opening 7 days a week would alter the working conditions of bakers and their teams, as well as the attractiveness of the profession," defends Franck Thomasse. However, the president has to deal with a growing number of violators of the rule... recognizing that its means of action remain limited. The Syndicate has thus given up prosecuting companies offering bread every day of the week, which would imply mobilizing procedural costs and contributing to the congestion of the judicial system. Beyond the legal aspect, this choice could simply be a matter of common sense: "The population of craftsmen and entrepreneurs is changing considerably in bakeries. We are now evolving with young professionals who want more freedom, in order to build their own business model without hindrance, according to their desires and their competitive environment," observes Paul Boivin.

Far from the image of a two-tier bakery, crushing independent artisans, this new freedom should allow everyone to flourish and be stimulated by competition. A horizon that does not yet seem close to us, as the war of models seems to be fuelled by the various actors involved... even though we should probably do everything possible to better defend the bread trades, well beyond the famous "7/7".