Rudy Guénaire: From Steak to Sketch

Co-founder of the burger chain PNY, this 38-year-old math whiz fulfilled his childhood dream a few years ago: launching his own design agency, where he creates both spaces and objects.

Co-founder of the burger chain PNY, this 38-year-old math whiz fulfilled his childhood dream a few years ago: launching his own design agency, where he creates both spaces and objects.

If the name “PNY (Paris New York)” rings a bell, it’s no surprise. The brand, created in 2012 by Graffi Rathamohan and his HEC business school friend Rudy Guénaire, was one of the key players in the “premiumization” of the burger in France. Today, eight locations are spread across Paris, with expansions into Strasbourg, Lille, Reims, Nantes, Lyon, and Bordeaux. According to Les Échos, the group posted €18 million in revenue in 2023, employs 200 people, and now has its sights set on Switzerland and Belgium.

After years of shadowing architects on site—from Paris-based studio CUT to Belgian designer Bernard Dubois, his collaborator on six or seven openings—Rudy became convinced he could cross over to the other side. In 2022, he founded Night Flight, a nod to Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Vol de nuit (1931, Gallimard). “There was still something unfulfilled in my mind,” he told L’Officiel in 2023. At age ten, he was already telling his parents he’d be a designer—a love of aesthetics nurtured by a mother who taught classical literature and a father who was both a lawyer and essayist, who took the family to museums and ancient ruins all over the world.

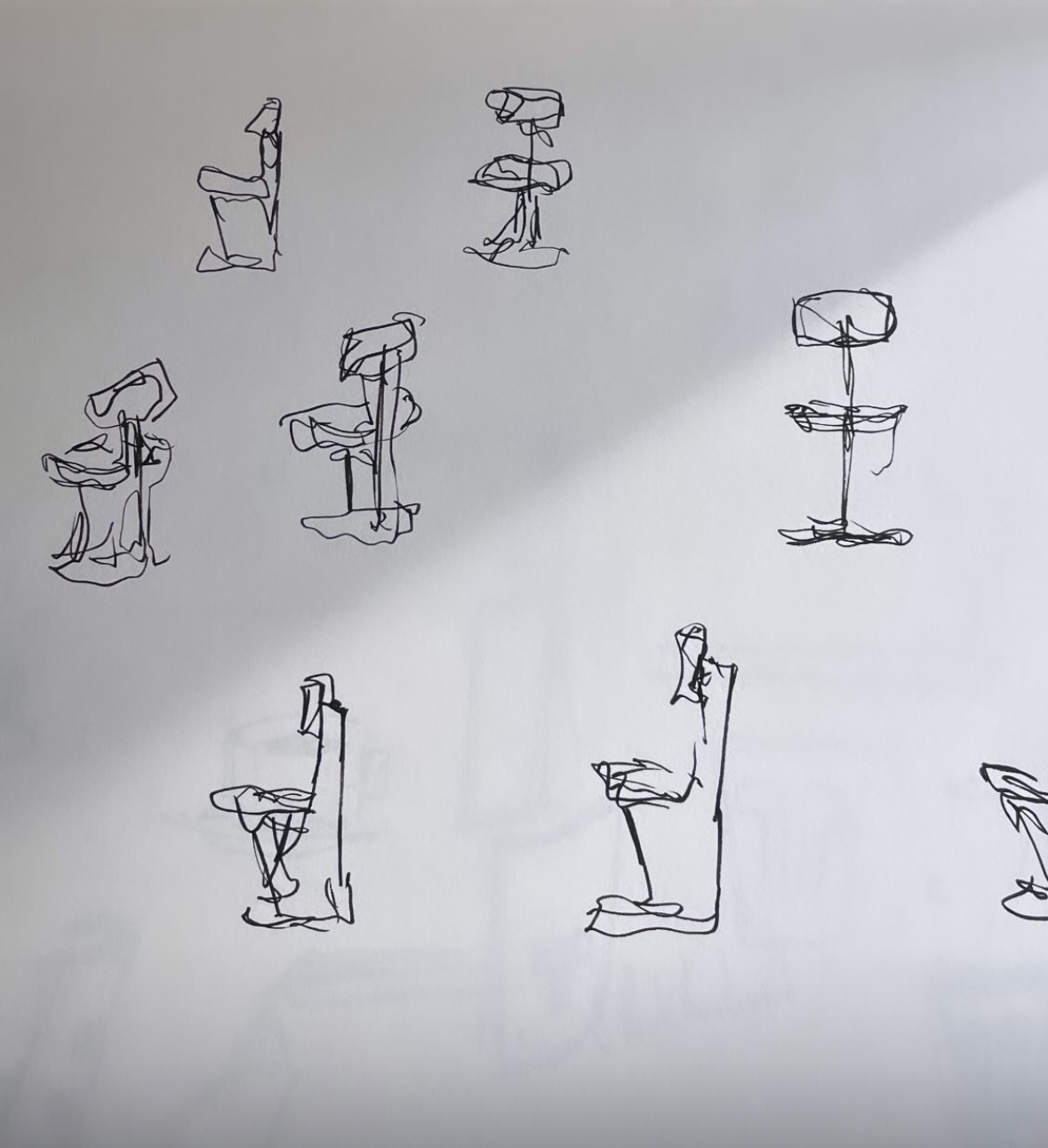

He doesn’t care about not mastering 3D software: he sketches by hand, convinced that the line matters more than the program. To shape the universe of his restaurants, he draws inspiration from cinema—a passion forged in a home with no television, and indulged at age 17 with a binge of Hitchcock, Kubrick, Bergman, and Lynch. “It’s easy to design a beautiful space using Pinterest and Instagram—you just build a moodboard from things you’ve grabbed left and right. Anyone can do it, you don’t need depth. That’s why so many restaurants look the same now... I wanted to design places where you could tell a story, like in a film—something truly unique.”

The results can be surprising. In Nantes, Yellowtrace wrote that “it feels like an Italian speedboat got lost and washed up in the turquoise waters of the Polynesian islands.” In Grenoble, giant airplane windows line the walls. Rudy Guénaire openly embraces a “small obsession with modernism” and explains: “After WWII, in the 1950s and ’60s, there was this pretty cool moment—society still blindly believed in progress, in the idea that happiness would come through it, and that we had to invent the house of tomorrow. So we got rid of grandpa’s old wallpaper and went for something airier, brighter. That era had this kind of innocence—with soft shapes, beautiful curves, diagonals, slanted lines, but always with a sense of gentleness.”

Among his influences: American architect John Lautner, a student of Frank Lloyd Wright. Just don’t mention Philippe Starck—he’s Rudy’s anti-model.

© Ludovic Balay

The founder of PNY designs lamps and coat racks—and dreams of creating cutlery: “There are very few beautiful cutlery sets out there, especially modern ones. No cutlery in the world is better designed than the Pearl collection by Austrian designer Josef Hoffmann.” Like Gio Ponti—“those guys who did graphic design, dinnerware, buildings…”—he dabbles in everything, though his real passion is for chairs. “I started sketching chairs without really knowing it’s one of the hardest things to design—because it’s all constraints: weight, stability. But I like equations with lots of unknowns. My Phoenix chair, for example—it’s a clean design, built around two sheets of aluminum. It was originally created for the PNY in Grenoble. A furniture publisher, La Chance, called me to propose a version for their catalog. The Beau Rivage chair is pretty cool too. It feels like it comes from the past, but there’s something a bit futuristic about it—it kind of leaves you lost in time.”

© Ludovic Balay

Another passion of his: wood. “I love it, and of course, I’m drawn to rich, precious woods. I just got back from Brazil and discovered jacaranda, which you’re no longer allowed to cut—it’s symbolically equivalent to the elephant in Africa. But it’s an unreal kind of beauty—dark, reddish, with infinite things happening in the grain. It’s the complete opposite of oak, which is the least exciting wood there is.

And wood has this powerful, feminine side. There’s nothing more immense, and yet its energy is warm, positive. Sometimes I run into clients who say they hate wood. That’s like saying you hate fries, jam, or the sun!”

In his view, restaurant lighting is severely underrated: “It’s super important, but in France, we don’t really know how to do it—unlike Brussels or Copenhagen. The only ones who do it well here are Studio KO, the firm behind Chiltern Firehouse in London, a former firehouse. The Anglo-Saxons invest real money and bring in LED designers who take all the materials and run them through some complex software.”

In his Paris apartment, he’s mounted Miguel Milá sconces with Soraa bulbs—“the best in the world!”

He stays away from trends by choice: “I don’t really keep up with what’s new—it wears me out. I need to live a bit in my own world.” He laments the global homogenization of design: “That’s the saddest part—you spend thirteen hours on a plane and find yourself in the exact same coffee shop. It hits me psychologically.”

His recent trip to Brazil—still relatively untouched by Western influence—felt like a breath of fresh air. In São Paulo, the Seen restaurant at the Tivoli Hotel “blew him away.” “It’s a bit like being in Batman.” In Europe, he praises the design direction of London-based restaurant group Bao: “In restaurant art direction in Europe, they’re the best in my opinion.”

Why does everything end up looking the same? He points to increasingly rigid regulations: “Certain materials now have to meet ERP (public building) standards so floors aren’t slippery. Back in the day, no one cared about the rules—that’s why all the hotels looked great. Now they use Oberflex, this plastic-coated wood that’s hideous and more expensive because it’s fire-resistant. Same with the banquettes—they all have to be fireproof now…”

Then there’s cost: “People walk into churches and marvel at the marble floors with incredible patinas. A real zinc counter in a bistro can last 130 years. But because investment funds only think five years ahead... that mindset ruins it.

That’s why I’m still fascinated by those moments in human history—like Notre-Dame de Paris—when people poured enormous resources into creating something extraordinary. We’ve kind of forgotten how to do that.”

By Pomélo